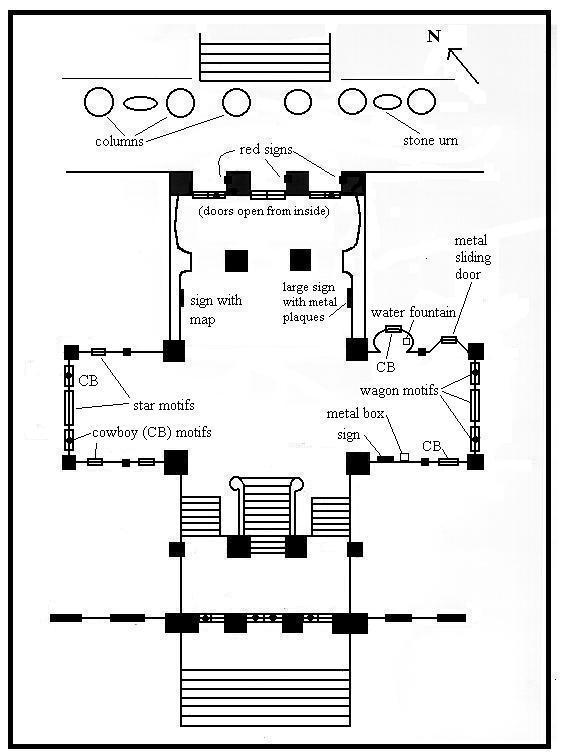

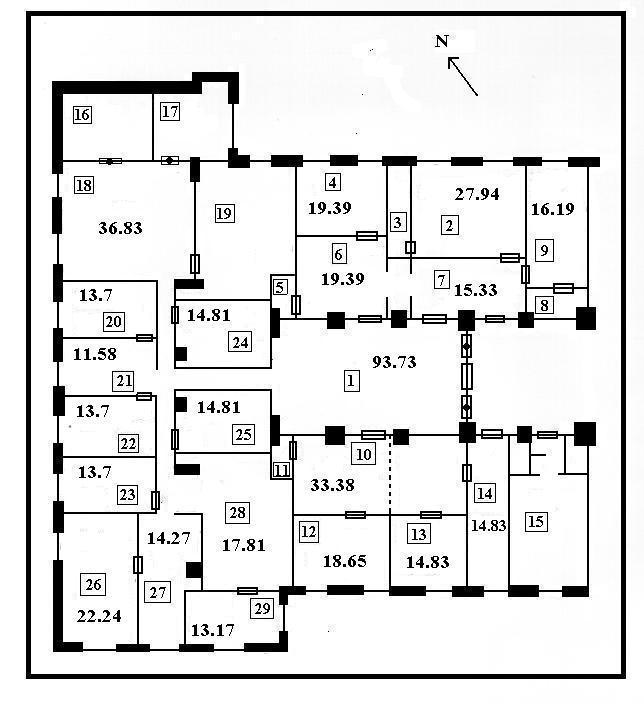

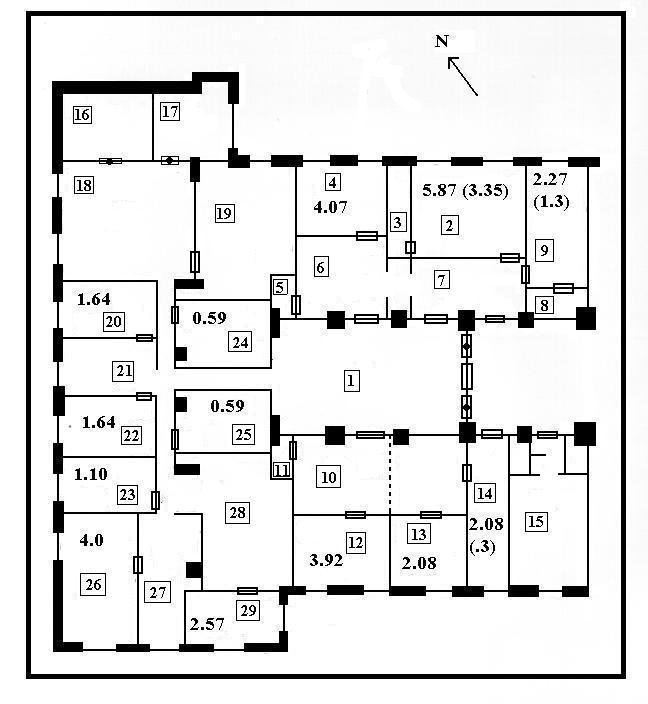

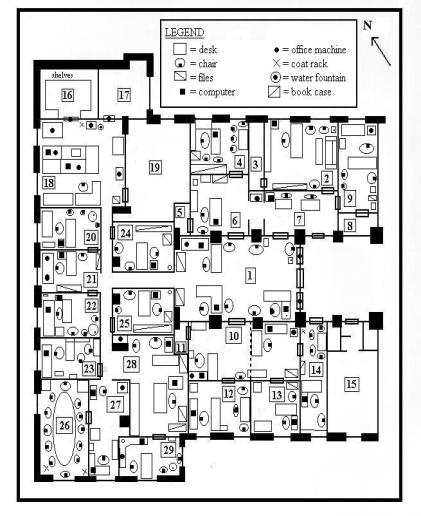

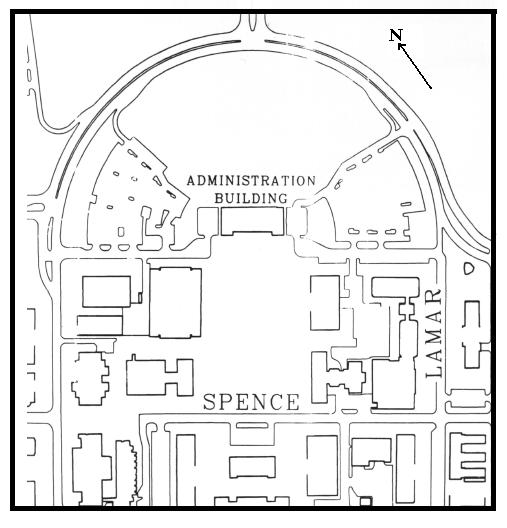

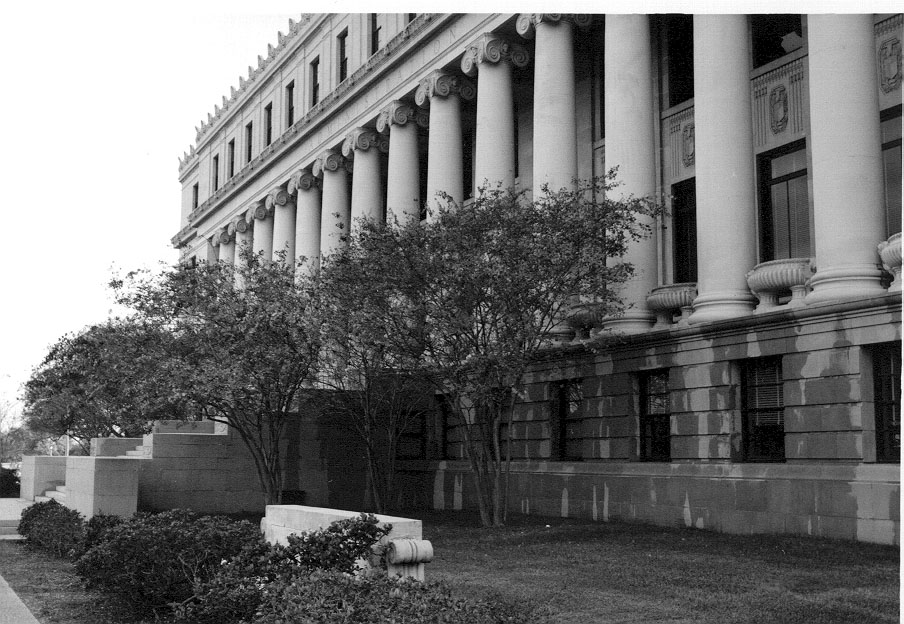

The structure commands the main east entrance to the complex. It stands at the head of a long, rectangular section of buildings and is flanked by two large paved areas (Figure 1). The main facade is fairly imposing, with a row of smooth ionic columns at the top of the stone steps, filling the space between the uppermost and the ground floors, with alternating male and female human faces at the tops of the columns (Figure 2).

Figure 1 |

Figure 2 |

Entering from the east, one must walk up 24 ash-gray stone steps divided into two levels. At the top, one is met by three pairs of metal double doors. The doors are very heavy, requiring a good deal of force to open. The middle door will only open from the inside, but the right-hand door of the left and right pairs will give way from the exterior. Red plastic rectangular signs with glyphic inscriptions and symbols, which seem to indicate that an activity involving combustion is prohibited, have been affixed next to the doors. One of these has been melted and burned. The top of each door features the image of a man using a scythe, wearing a hat and boots, depicted in metal. Above each of the two side doors is an image of a man etched in the stone, with glyphic letters beneath. One appears to be a hunter or frontiersman, and holds a rifle and what may be a script. The other appears to be a statesman and holds what looks like a scroll. Above the middle doors is the image of a man who seems to be a farmer and a man who seems to be a rancher kneeling face to face before a seated female figure, which appears serene but stern (Figure 3). A star graces her head, and she holds a staff in her right hand and what seems to be fruit in her left, resting on her lap. Perhaps the female figure represents justice in a union between farmers and ranchers. Above the windows, along the facade behind the columns, are cow skull images surrounded by agricultural products, with stars and geometric forms. These various agricultural images on the building’s exterior suggest that some agricultural administrative function is carried on inside.